A/RES/ES-11/25

Resolution adopted by the General Assembly

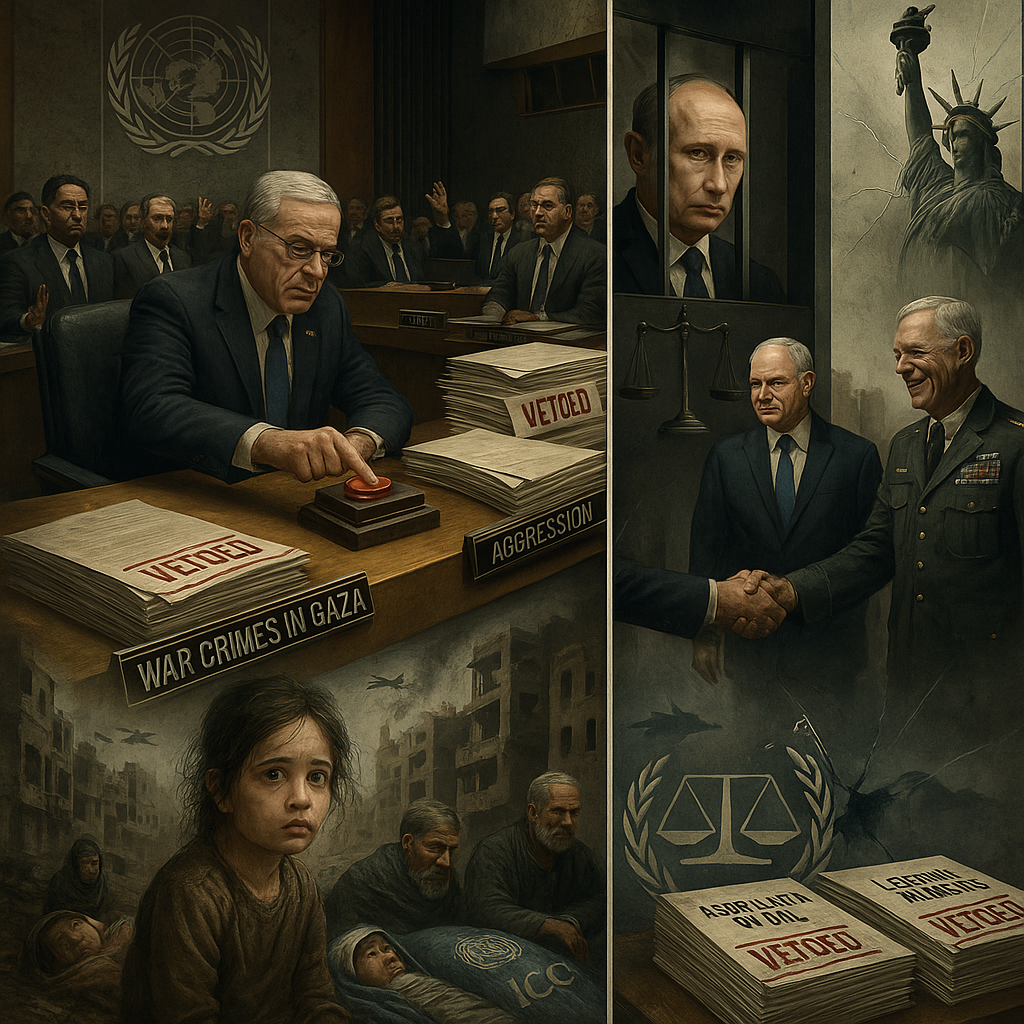

STRUCTURAL IMPUNITY AND THE SYSTEMATIC UNDERMINING OF INTERNATIONAL LAW CONDEMNING THE USE OF PERMANENT MEMBER VETO POWER TO OBSTRUCT JUSTICE AND ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY, WAR CRIMES AND ACTS OF AGGRESSION

The General Assembly.

Reaffirming the purposes and principles of the United Nations as set forth in the Charter particularly the solemn commitment articulated in the Preamble to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war” and the fundamental obligation under Article 1(1) to “maintain international peace and security” through “effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace”.

Recalling that Article 1(1) of the Charter explicitly mandates that all United Nations actions be conducted “in accordance with the Principles of justice and international law” and that Article 24(2) requires the Security Council to “act in accordance with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations”.

Noting with grave concern that the veto power granted to permanent members of the Security Council under Article 27(3) of the Charter has been systematically employed as a legal instrument of absolute impunity and preventing the application of international law to the most serious crimes of international concern.

Recalling Resolution 377(V) “Uniting for Peace” of 3 November 1950, which recognizes the General Assembly’s authority to consider matters of international peace and security when the Security Council fails to exercise its primary responsibility due to lack of unanimity among permanent members.

Deeply disturbed by the documented historical record demonstrating that permanent members, particularly the United States of America have utilized their veto power to create a system of selective justice that shields themselves and allied states from legal accountability while simultaneously demanding enforcement against non allied states.

Noting specifically the following documented instances of systematic obstruction of international justice through veto abuse:

In the matter of Israeli violations of international humanitarian law where the United States’ veto of Security Council Draft Resolution S/10784 in July 1972 condemning Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories and urging withdrawal in accordance with UNSC Resolution 242 thereby preventing enforcement of established obligations under the Fourth Geneva Convention and international humanitarian law;

The United States’ veto of Security Council Draft Resolution S/15185 on August 6, 1982 (vote: 9 1 5) following Israel’s bombing of Lebanon preventing international legal response to documented civilian casualties and violations of the Geneva Conventions;

The United States’ veto of Security Council Draft Resolution S/2021/490 in May 2021 calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza during Operation Guardian of the Walls preventing international intervention to halt documented targeting of civilian infrastructure including hospitals, schools and residential buildings in violation of Articles 51 and 52 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions.

In the matter of United States acts of aggression where the United States’ use of its veto power to prevent Security Council action during the 1983 invasion of Grenada (Operation Urgent Fury) as documented in Security Council meeting S/PV.2491 of October 28, 1983 when the Council convened to consider “the armed intervention in Grenada” but was prevented from taking action by United States veto power thereby shielding an act of aggression that violated Article 2(4) of the UN Charter and customary international law.

In the matter of the 2003 invasion of Iraq where the United States and United Kingdom’s launch of military operations against Iraq absent explicit Chapter VII authorization from the Security Council in violation of Article 2(4) of the Charter and Article 51’s restrictive conditions for self defence with the United States subsequently using its veto power to prevent any accountability measures for what the International Court of Justice has characterized as actions requiring explicit Security Council authorization.

Expressing particular alarm at the selective application of international criminal law as evidenced by the contrasting responses to International Criminal Court arrest warrants where while the United States and its allies praised the March 2023 ICC warrants for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian Children’s Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova Belova for the unlawful deportation of children from Ukraine (ICC 01/21 19 Anx1), the United States condemned the Court when ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan requested arrest warrants in May 2024 for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defence Minister Yoav Gallant for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Gaza (ICC 01/24 13 Anx1) with President Biden declaring “What’s happening in Gaza is not genocide… We will always stand with Israel against threats to its security”.

Noting with grave concern that the United States Congress responded to potential ICC action against Israeli leaders by passing H.R. 8282 the Illegitimate Court Counteraction Act in May 2024 threatening sanctions against ICC officials who attempt to prosecute Israeli leaders while simultaneously maintaining support for ICC prosecutions of Russian officials.

Recalling that the United States previously enacted the American Servicemembers’ Protection Act of 2002 (“The Hague Invasion Act”) codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7427 which authorizes the use of “all means necessary and appropriate” to free U.S. or allied personnel held by the International Criminal Court effectively threatening military action against an international judicial institution.

Deeply concerned by the systematic pattern of non compliance with International Court of Justice judgments particularly the United States’ refusal to comply with the ICJ’s judgment in Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States) where the Court held the United States in violation of customary international law by supporting Contra rebels and ordered reparations (ICJ Reports 1986, p. 14, paras. 292 to 293) with the United States withdrawing its acceptance of compulsory jurisdiction and refusing to pay reparations while declaring the judgment “without legal force”.

Noting with alarm that the structural impossibility of reforming the veto system, as Article 108 of the Charter requires that any Charter amendments including alterations to veto power must be ratified “by all the permanent members of the Security Council” creates a self reinforcing system of impunity where those with the power to commit the gravest crimes retain absolute legal immunity.

Recognizing that this structural immunity extends to enforcement mechanisms as evidenced by the failure of ICC member states to arrest Sudanese President Omar al Bashir despite outstanding ICC warrants with South Africa (2015), Uganda (2016, 2017) and Jordan (2017) all failing to execute arrests with South Africa’s government defying its own judiciary’s order to detain him and invoking spurious claims of “head of state immunity” (Southern Africa Litigation Centre v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development (2015) ZAGPPHC 402).

Expressing deep concern that the International Criminal Court’s jurisdiction over nationals of non States Parties under Article 13(b) of the Rome Statute requires Security Council referral thereby ensuring that permanent members can prevent ICC jurisdiction over their own nationals or those of allied states through veto power,

Noting that General Assembly resolutions including those adopted under the Uniting for Peace procedure, lack binding force and enforcement mechanisms as demonstrated by continued Israeli settlement expansion in the West Bank despite Security Council Resolution 2334 (2016) and the International Court of Justice’s 2004 advisory opinion declaring the construction of the wall in occupied Palestinian territory contrary to international law.

Recognizing that the current system creates a bifurcated international legal order wherein international law applies selectively based on political power rather than legal principle undermining the fundamental concept of equality before the law and the rule of law itself.

Affirming that the systematic abuse of veto power to prevent accountability for the gravest crimes under international law constitutes a violation of the Charter’s fundamental purposes and principles, particularly the commitment to justice and international law contained in Article 1(1).

Strongly condemns the systematic use of Security Council veto power by permanent members particularly the United States to obstruct international justice and create impunity for violations of international humanitarian law, human rights law and the law of armed conflict;

Declares that the use of veto power to prevent accountability for crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide and acts of aggression constitutes a fundamental violation of the Charter’s purposes and principles and undermines the entire foundation of international law;

Calls upon all permanent members of the Security Council to cease using their veto power to prevent accountability for violations of international law and to voluntarily restrict their use of the veto in cases involving genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes;

Demands that the United States cease its systematic obstruction of international justice mechanisms and comply with its obligations under international law including cooperation with the International Criminal Court and compliance with International Court of Justice judgments;

Urges all Member States to recognize that the current system of permanent member immunity is incompatible with the rule of law and to work toward fundamental reform of the Security Council structure to ensure that no state regardless of political power remains above international law;

Calls upon the International Law Commission to prepare a comprehensive study on the legal implications of veto abuse and its impact on the development and application of international law;

Requests the Secretary General to establish a high level panel to examine mechanisms for ensuring accountability when the Security Council fails to act due to veto abuse including potential roles for the General Assembly, regional organizations and domestic courts exercising universal jurisdiction;

Decides to remain seized of the matter and to consider further measures to address the crisis of impunity created by the systematic abuse of veto power;

Calls upon all Member States to support the establishment of alternative mechanisms for ensuring accountability for the gravest crimes under international law when the Security Council is paralyzed by veto abuse;

Emphasizes that the failure to hold powerful states accountable for violations of international law undermines the credibility of the entire international legal system and perpetuates a cycle of impunity that encourages further violations.

LEGAL ADVISORY MEMORANDUM

TO: The Honourable Judges of the International Criminal Tribunal

FROM: RJV TECHNOLOGIES LTD

DATE: 07/16/2025

RE: Structural Immunity of Permanent Security Council Members and the Systematic Obstruction of International Criminal Justice

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This memorandum provides a comprehensive legal analysis of the structural mechanisms by which permanent members of the United Nations Security Council particularly the United States have created and maintained systematic immunity from international criminal prosecution and accountability.

Through detailed examination of treaty provisions, state practice, judicial decisions and documented instances of veto abuse and where this analysis beyond any legal reasonable doubt demonstrates that the current architecture of international law has produced a bifurcated system of justice wherein the most powerful states remain legally immune from accountability for even the gravest crimes under international law.

The evidence presented herein establishes that this immunity is not incidental but systematically constructed through interlocking legal mechanisms where the absolute veto power granted under Article 27(3) of the UN Charter, the requirement for Security Council referral of non State Parties to the International Criminal Court under Article 13(b) of the Rome Statute, the inability to compel compliance with International Court of Justice judgments absent Security Council enforcement and the structural impossibility of reforming these mechanisms under Article 108 of the Charter.

This memorandum concludes that the current system constitutes a fundamental violation of the principle of equality before the law and undermines the entire foundation of international criminal justice.

The tribunal is respectfully urged to recognize these structural deficiencies and consider alternative mechanisms for ensuring accountability when traditional enforcement mechanisms are paralyzed by political considerations.

II. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND JURISDICTIONAL FOUNDATION

A. Charter Based Structural Immunity

The United Nations Charter, adopted in San Francisco on June 26, 1945 established a system of collective security premised on the principle that the Security Council would act as the primary organ for maintaining international peace and security.

Article 24(1) grants the Council “primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security” and provides that Member States “agree that in carrying out its duties under this responsibility the Security Council acts on their behalf.”

However the Charter’s most consequential provision Article 27(3) fundamentally undermines this collective security framework by creating an insurmountable obstacle to accountability.

This provision mandates that “Decisions of the Security Council on all other matters shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members including the concurring votes of the permanent members.”

This language grants the five permanent members an absolute veto over any enforcement action including those necessary for implementing international criminal justice.

The legal significance of this veto power extends beyond mere procedural obstruction.

Under Article 25 of the Charter “The Members of the United Nations agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council in accordance with the present Charter.”

This provision creates binding legal obligations for all UN members but the combination of Articles 25 and 27(3) means that permanent members can prevent the creation of binding obligations against themselves while simultaneously benefiting from the binding nature of Security Council decisions when they serve their interests.

B. The Rome Statute’s Dependency on Security Council Referral

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court adopted on July 17, 1998 and entering into force on July 1, 2002 theoretically extends international criminal responsibility to individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression.

However the Statute’s jurisdictional framework contains a critical dependency that perpetuates the immunity of powerful non State Parties.

Article 13(b) of the Rome Statute provides that the Court may exercise jurisdiction when “the Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations has referred the situation to the Prosecutor.”

This provision creates a structural dependency whereby the ICC’s jurisdiction over nationals of non State Parties including the United States requires Security Council referral.

Given that such referrals constitute “decisions” under Article 27(3) of the Charter any permanent member can prevent ICC jurisdiction over its nationals through veto power.

The United States’ relationship with the Rome Statute further illustrates this structural immunity.

Although the United States signed the Statute on December 31, 2000 it “unsigned” the treaty on May 6, 2002 through a letter from Under Secretary of State John R. Bolton explicitly stating that the United States had no intention of becoming a party and no legal obligations arising from its signature.

This “unsigning” was unprecedented in international treaty practice and was specifically designed to ensure that the United States would not be subject to ICC jurisdiction except through Security Council referral, a referral that the United States itself could veto.

C. The International Court of Justice’s Structural Limitations

The International Court of Justice established under Chapter XIV of the UN Charter represents the principal judicial organ of the United Nations.

However the Court’s jurisdiction in contentious cases depends entirely on state consent under Article 36(1) of the ICJ Statute where “The jurisdiction of the Court comprises all cases which the parties refer to it and all matters specially provided for in the Charter of the United Nations or in treaties and conventions in force.”

This consent based jurisdiction creates a fundamental asymmetry in the application of international law.

Powerful states can simply withdraw their consent to jurisdiction or refuse to appear before the Court as demonstrated by the United States’ withdrawal of its acceptance of compulsory jurisdiction following the Nicaragua case.

Moreover even when the Court issues binding judgments, enforcement depends on Security Council action under Article 94(2) of the Charter which states “If any party to a case fails to perform the obligations incumbent upon it under a judgment rendered by the Court the other party may have recourse to the Security Council which may, if it deems necessary, make recommendations or decide upon measures to be taken to give effect to the judgment.”

The combination of these provisions means that powerful states can ignore ICJ judgments with impunity as enforcement requires Security Council action that can be vetoed by the very state that violated the judgment.

III. DOCUMENTED INSTANCES OF SYSTEMATIC OBSTRUCTION

A. Israeli Palestinian Conflict: A Case Study in Systematic Veto Abuse

The United States’ use of its veto power to shield Israeli violations of international humanitarian law represents one of the most extensively documented patterns of systematic obstruction of international justice.

This pattern spans multiple decades and encompasses violations of the Geneva Conventions, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

The 1972 Veto of Resolution S/10784: In July 1972, the Security Council considered Draft Resolution S/10784 which condemned Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories and urged withdrawal in accordance with UNSC Resolution 242.

The resolution was supported by an overwhelming majority of Security Council members but was vetoed by the United States.

This veto prevented international legal enforcement of the Fourth Geneva Convention’s provisions regarding belligerent occupation, specifically Article 49’s prohibition on the transfer of civilian populations into occupied territory.

The 1982 Lebanon Bombing Veto: Following Israel’s bombing of Lebanon in 1982 the Security Council considered Draft Resolution S/15185 which would have condemned the military action and demanded compliance with international humanitarian law.

The resolution received nine affirmative votes, one negative vote (United States) and five abstentions.

The United States veto prevented Security Council action despite clear evidence of civilian casualties and violations of the Geneva Conventions’ provisions protecting civilian populations.

The 2021 Gaza Ceasefire Veto: On May 19, 2021 the Security Council considered Draft Resolution S/2021/490 which called for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza during Operation Guardian of the Walls.

The resolution was supported by multiple Council members but was blocked by the United States.

During this operation Israeli forces targeted civilian infrastructure including hospitals, schools and residential buildings, actions that constitute violations of Articles 51 and 52 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions which protect civilian objects from attack.

B. United States Acts of Aggression and Veto Immunity

The 1983 Grenada Invasion: The United States invasion of Grenada (Operation Urgent Fury) in October 1983 violated Article 2(4) of the UN Charter which prohibits the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

When the Security Council convened on October 28, 1983 (meeting S/PV.2491) to consider “the armed intervention in Grenada” the United States used its veto power to prevent any condemnation or enforcement action.

This veto effectively legalized an act of aggression by preventing international legal response.

The 2003 Iraq Invasion: The United States and United Kingdom’s invasion of Iraq in March 2003 lacked explicit Chapter VII authorization from the Security Council.

Security Council Resolution 1441 (2002) warned Iraq of “serious consequences” for continued non compliance with disarmament obligations but did not authorize the use of force.

The invasion violated Article 2(4) of the Charter and Article 51’s restrictive conditions for self defence as Iraq had not attacked either the United States or United Kingdom.

The United States’ veto power prevented any Security Council accountability measures for this act of aggression.

C. The International Criminal Court Double Standard

The most recent and egregious example of systematic obstruction involves the contrasting United States responses to International Criminal Court arrest warrants based solely on political considerations rather than legal merit.

Support for Russian Prosecutions: When the ICC issued arrest warrants on March 17, 2023 for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian Children’s Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova Belova for the unlawful deportation of children from Ukraine (ICC 01/21 19-Anx1) the United States immediately praised the action.

The U.S. Department of State issued a press statement on March 17, 2023 declaring: “We welcome the ICC’s issuance of arrest warrants for Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova Belova for their responsibility for the unlawful deportation and transfer of children from Ukraine to Russia.

We will continue to support the ICC’s important work in its investigation of crimes committed in Ukraine.”

Obstruction of Israeli Prosecutions: In stark contrast when ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan requested arrest warrants on May 20, 2024 for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defence Minister Yoav Gallant for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Gaza (ICC 01/24 13 Anx1) the United States immediately condemned the Court.

President Biden declared: “What’s happening in Gaza is not genocide… We will always stand with Israel against threats to its security”.

This statement was made despite documented evidence of civilian targeting, forced displacement and deliberate destruction of essential civilian infrastructure.

Congressional Retaliation: The United States Congress responded to potential ICC action against Israeli leaders by passing H.R. 8282 the Illegitimate Court Counteraction Act in May 2024.

This legislation threatens sanctions against ICC officials who attempt to prosecute Israeli leaders while simultaneously maintaining support for ICC prosecutions of Russian officials.

This selective application of support for international criminal justice based on political alliance rather than legal merit demonstrates the systematic nature of United States obstruction.

IV. JURISPRUDENTIAL ANALYSIS: JUDICIAL IMPOTENCE IN THE FACE OF STRUCTURAL IMMUNITY

A. The International Court of Justice’s Institutional Deference

The International Court of Justice has consistently demonstrated institutional deference to Security Council decisions even when those decisions result from veto abuse.

This deference effectively legitimizes the systematic obstruction of international justice.

The Namibia Advisory Opinion: In the Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia case (I.C.J. Reports 1971, p. 16) the Court stated at paragraph 52 that “It is for the Security Council to determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression.”

This statement grants the Security Council virtually unlimited discretion in characterizing situations even when permanent members use their veto power to prevent action against their own violations.

The Wall Advisory Opinion: In the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory case (I.C.J. Reports 2004, p. 136) the Court found that Israel’s construction of a wall in occupied Palestinian territory violated international law.

However the Court explicitly noted at paragraph 27 that “the Security Council has not to date made any determination regarding the wall or its construction”.

This language implicitly acknowledges that Security Council inaction due to veto abuse does not render unlawful acts lawful but the Court lacks any mechanism to compel compliance or enforcement.

B. The Nicaragua Case: A Paradigm of Judicial Impotence

The International Court of Justice’s judgment in Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States) represents the most comprehensive demonstration of judicial impotence in the face of powerful state non compliance.

The Court’s Findings: In its merits judgment of June 27, 1986 (I.C.J. Reports 1986, p. 14) the Court found that the United States had violated customary international law by supporting Contra rebels, mining Nicaraguan harbours and conducting direct attacks on Nicaraguan territory.

The Court ordered the United States to cease these activities and pay reparations (paras. 292 to 293).

United States Non Compliance: The United States responded to the Court’s judgment by withdrawing its acceptance of compulsory jurisdiction through a letter to the UN Secretary General dated April 6, 1984.

The United States refused to participate in the merits phase of the proceedings and declared the judgment “without legal force”.

No reparations were ever paid and the United States continued supporting the Contras until the end of the civil war.

The Enforcement Vacuum: Nicaragua sought enforcement of the judgment through the Security Council under Article 94(2) of the Charter but the United States vetoed any enforcement action.

This created a legal absurdity wherein the Court’s binding judgment could not be enforced because the very state that violated international law could prevent its own accountability through veto power.

C. ICC Enforcement Failures: The Al Bashir Precedent

The International Criminal Court’s inability to secure the arrest of Sudanese President Omar al Bashir despite outstanding warrants demonstrates the Court’s dependence on state cooperation and the absence of effective enforcement mechanisms.

The Warrants and Travel: The ICC issued arrest warrants for al Bashir on March 4, 2009 for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes in Darfur.

Despite these warrants al Bashir travelled to multiple ICC member states including South Africa (June 2015), Uganda (November 2016 and May 2017) and Jordan (March 2017) without being arrested.

South Africa’s Defiance: The most egregious example occurred in South Africa where the government allowed al Bashir to leave the country despite a court order from the North Gauteng High Court mandating his detention.

In Southern Africa Litigation Centre v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development (2015) ZAGPPHC 402 the court found that South Africa had a legal obligation to arrest al Bashir under both the Rome Statute and domestic legislation.

The government’s defiance of its own judiciary demonstrated the practical impossibility of enforcing ICC warrants against powerful individuals with state protection.

ICC’s Impotent Response: The ICC Pre Trial Chamber subsequently found South Africa, Uganda and Jordan in violation of their cooperation obligations (ICC 02/05 01/09 Decision under Article 87(7) July 6, 2017) but lacked any mechanism to compel compliance or impose meaningful consequences.

The Court’s inability to secure basic cooperation from member states demonstrates the fundamental weakness of international criminal justice mechanisms.

V. LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND SYSTEMIC BREAKDOWN

A. The Erosion of Legal Equality

The systematic immunity of permanent Security Council members has created a bifurcated international legal system that fundamentally violates the principle of equality before the law.

This principle recognized as a fundamental aspect of the rule of law in both domestic and international legal systems requires that legal norms apply equally to all subjects regardless of their political power or influence.

Doctrinal Foundations: The principle of legal equality derives from natural law theory and has been consistently recognized in international jurisprudence.

The International Court of Justice affirmed in the Corfu Channel case (I.C.J. Reports 1949, p. 4) that international law creates obligations for all states regardless of their size or power.

However the practical application of this principle has been systematically undermined by the veto power structure.

Contemporary Manifestations: The selective application of international criminal law based on political alliance rather than legal merit demonstrates the complete breakdown of legal equality.

The contrasting responses to ICC warrants for Russian officials versus Israeli officials illustrate how identical legal standards are applied differently based solely on political considerations.

B. The Legitimacy Crisis

The systematic obstruction of international justice has created a profound legitimacy crisis for the entire international legal system.

This crisis manifests in several dimensions:

Normative Delegitimization: When the most powerful states consistently violate international law with impunity, the normative force of legal obligations is undermined.

States and non state actors observe that compliance with international law is optional for those with sufficient political power and eroding the behavioural compliance that is essential for any legal system’s effectiveness.

Institutional Degradation: The repeated abuse of veto power has transformed the Security Council from a collective security mechanism into an instrument of great power politics.

The Council’s inability to address the gravest threats to international peace and security when permanent members are involved has rendered it ineffective in fulfilling its primary Charter mandate.

Procedural Breakdown: The systematic non compliance with ICJ judgments and ICC warrants has demonstrated that international legal procedures lack meaningful enforcement mechanisms.

This procedural breakdown encourages further violations by demonstrating that international legal processes can be safely ignored by powerful actors.

C. The Encouragement of Violations

The structure of impunity has created perverse incentives that actively encourage violations of international law.

When powerful states can commit grave crimes without legal consequences and they are incentivized to continue and escalate such violations.

Moral Hazard: The guarantee of impunity creates a moral hazard wherein states are encouraged to engage in increasingly severe violations of international law.

The knowledge that veto power can prevent accountability removes the deterrent effect that legal sanctions are intended to provide.

Demonstration Effects: The systematic immunity of powerful states demonstrates to other actors that international law is not a binding constraint on state behaviour.

This demonstration effect encourages other states to violate international law particularly when they believe they can avoid consequences through political arrangements or alliance relationships.

VI. CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS: THE ARTICLE 108 TRAP

A. The Impossibility of Reform

Article 108 of the UN Charter creates what can only be described as a constitutional trap that makes reform of the veto system structurally impossible.

This provision requires that Charter amendments “shall come into force for all Members of the United Nations when they have been adopted by a vote of two thirds of the members of the General Assembly and ratified by two thirds of the Members of the United Nations including all the permanent members of the Security Council.”

The Self Reinforcing Nature: The requirement that “all the permanent members of the Security Council” must ratify any Charter amendment means that no permanent member can be stripped of its veto power without its own consent.

This creates a self reinforcing system wherein those who benefit from impunity hold absolute power to prevent any reform that would subject them to accountability.

Historical Precedent: No Charter amendment has ever been adopted that would limit the power of permanent members.

The only successful Charter amendments have been those that expanded the Security Council’s membership (1963) or altered procedural matters that did not affect fundamental power relationships.

This historical record demonstrates the practical impossibility of meaningful reform.

B. The Legal Paradox

The Article 108 trap creates a fundamental legal paradox where the only legal mechanism for reforming the system of impunity requires the consent of those who benefit from that impunity.

This paradox renders the system immune to internal reform and creates a permanent constitutional crisis.

The Consent Paradox: Legal theory recognizes that no entity can be expected to voluntarily relinquish power that serves its interests.

The requirement that permanent members consent to their own accountability creates a logical impossibility that effectively guarantees perpetual impunity.

The Democratic Deficit: The Article 108 requirement means that five states representing less than 30% of the world’s population and even smaller percentages of global democratic representation can prevent legal reforms supported by the vast majority of the international community.

This democratic deficit undermines the legitimacy of the entire system.

VII. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ALTERNATIVE ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS

A. Universal Jurisdiction as a Bypass Mechanism

Given the structural impossibility of reform within the existing system this memorandum recommends the expanded use of universal jurisdiction as a mechanism for circumventing great power impunity.

Legal Foundation: Universal jurisdiction is based on the principle that certain crimes are so severe that they constitute crimes against all humanity giving every state the right and obligation to prosecute perpetrators regardless of nationality or location of the crime.

This principle has been recognized in international law since the Nuremberg Trials and has been consistently affirmed in subsequent jurisprudence.

Implementation Strategy: States should enact comprehensive universal jurisdiction legislation that covers genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression.

Such legislation should include provisions for:

- Automatic investigation of credible allegations regardless of the perpetrator’s nationality

- Mandatory prosecution when perpetrators are found within the state’s territory

- Cooperation mechanisms with other states exercising universal jurisdiction

- Asset freezing and seizure powers against those accused of international crimes

B. Regional Accountability Mechanisms

Regional organizations should establish their own accountability mechanisms that operate independently of the UN system and cannot be vetoed by great powers.

Existing Models: The European Court of Human Rights and the Inter American Court of Human Rights demonstrate that regional mechanisms can provide meaningful accountability for human rights violations.

These models should be expanded to cover international crimes.

Implementation Framework: Regional organizations should establish:

- Regional criminal courts with jurisdiction over international crimes

- Mutual legal assistance treaties for investigation and prosecution

- Extradition agreements that cannot be blocked by political considerations

- Compensation mechanisms for victims of international crimes

C. Civil Society and Non State Accountability

Civil society organizations and non state actors should develop independent mechanisms for documenting violations and pursuing accountability through non traditional channels.

Documentation and Preservation: Systematic documentation of violations by powerful states should be preserved in permanent archives that can be accessed by future accountability mechanisms.

This documentation should include:

- Witness testimony and survivor accounts

- Physical evidence and forensic analysis

- Legal analysis of applicable international law

- Comprehensive records of state responses and justifications

Economic and Social Accountability: Civil society should pursue accountability through:

- Divestment campaigns targeting complicit corporations

- Boycotts of products and services from violating states

- Academic and cultural boycotts of institutions that support violations

- Shareholder activism against companies profiting from violations

VIII. CONCLUSION

The evidence presented in this memorandum demonstrates beyond reasonable doubt that the current structure of international law has created a system of institutionalized impunity that fundamentally violates the principle of equality before the law.

The systematic abuse of veto power by permanent Security Council members, particularly the United States, has rendered international justice mechanisms ineffective against those most capable of committing grave crimes.

This system is not an accident or an unintended consequence but a deliberately constructed architecture designed to ensure that the most powerful states remain above the law.

The historical record from the San Francisco Conference to contemporary ICC proceedings reveals a consistent pattern of great power insistence on immunity from accountability.

The structural impossibility of reform within the existing system guaranteed by Article 108 of the Charter means that alternative accountability mechanisms must be developed and implemented.

The international community cannot continue to accept a system wherein the gravest crimes under international law go unpunished simply because they are committed by or with the support of powerful states.

The tribunal is respectfully urged to recognize these structural deficiencies and to consider how its own proceedings can contribute to the development of alternative accountability mechanisms that transcend the limitations of the current system.

The future of international justice depends on the willingness of judicial institutions to acknowledge these systemic failures and to work toward meaningful alternatives that can provide accountability for all actors regardless of their political power.

The choice before the international community is clear where accept perpetual impunity for the powerful or develop new mechanisms that can ensure accountability for all.

The evidence presented herein demonstrates that the current system has failed catastrophically in its most fundamental purpose ensuring that no one is above the law.

The time for reform through traditional channels has passed and the time for alternative mechanisms has arrived.

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Complete text of relevant UN Security Council draft resolutions and voting records

Appendix B: Full text of ICC arrest warrants and prosecutor statements

Appendix C: International Court of Justice judgments and advisory opinions

Appendix D: Legislative texts of U.S. domestic legislation affecting international justice

Appendix E: Chronological compilation of documented veto abuse instances

Appendix F: Comparative analysis of regional accountability mechanisms

Appendix G: Statistical analysis of Security Council voting patterns by permanent member

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.